Interoperability is often touted as the most important consideration in building the Metaverse. While this statement looks obvious at first glance, it actually requires more analysis. And, in the Acceleration Economy, nothing is safe from deconstruction and questioning—including interoperability.

However, not all answers can be explained through analysis like this. Yes, a virtual concept is at the center of this post, but collaboration with the physical world brings real life insights into how the future is optimized for your organization.

Register today to join me and my Acceleration Economy Analyst colleagues at Cloud Wars Expo – June 28-30 – where the Metaverse will be a core category.

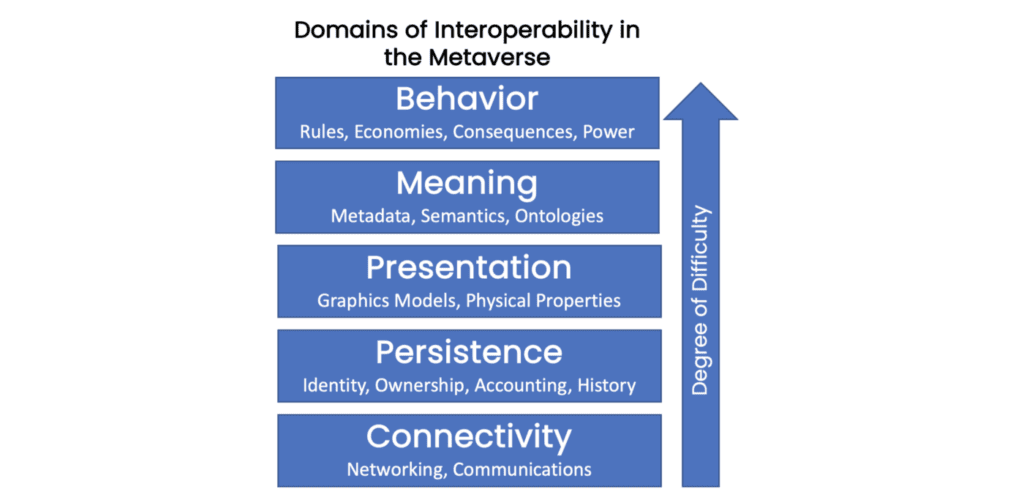

5 Domains of Interoperability

First, what does it even mean? Game developer and CEO of Beamable.com, Jon Radoff, points out that there are multiple layers of the Metaverse that need to interoperate:

Technical Connectivity

The first is the most obvious: technical connectivity. Luckily, the spatial Internet will most likely rely on the same protocols and languages of the current Internet, such as TCP/IP, HTTP(S), REST, HTML, etc, which are already open.

Persistence

The next layer is what he calls persistence, or maintaining state. This refers to storing knowledge of who owns what, what is where, and how things are. In a centralized model, like that of Meta’s Horizon Worlds, all of this information is stored in company-owned servers and kept under lock-and-key.

However, proponents of blockchain believe the technology will change how the persistence problem is tackled in the Metaverse by offering decentralized storage of data. Any applications built on top of the blockchain share the same immutable, agreed-upon set of data regarding ownership and state, elements that are key to making an economy function.

Presentation

The next layer is presentation, which has more to do with “divergent design goals” in the words of Radoff. Will worlds look blocky like Minecraft or photorealistic like Metahumans? Unfortunately, enforcing everyone to have the same design palette is very difficult.

While there’s no issue in having some variation in presentation, especially in niche applications, the subworlds of the Metaverse experiencing the most user traffic interchange on a day-to-day basis should consider homogenizing their aesthetic.

Meaning

The layers following the presentation layer are harder to grasp but equally as important. Radoff points out that meaning won’t necessarily be equal across virtual worlds. For example, equip your avatar with a wizard’s robe. In one world, this might mean you’re a student of Hogwarts, but in another, you’re dressing up for Halloween.

Behavior

The final layer is behavior. “Whereas the persistence domain provides the ability to preserve the state of the economy, the actual economy rises out of all of the behaviors that happen within a world or across multiple cooperating worlds,” says Radoff.

In essence, this is culture. For example, what one gesture means in one part of the world doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing in another. It is impossible to homogenize meaning and behavior across the spatial Internet just as it is across the current Internet and the world at large. However, it’s still useful to consider as a form of interoperability that will shape how certain facets of the Metaverse can operate.

Asimov and others have pointed out that it’s easy to predict technology, but it’s very hard to predict how that technology will be used and how it will mold around society.

Interoperability as a Mindset

Finally, I would argue that interoperability is also a mindset. The only reason humanity is where it is right now is that innovations can build on top of each other. Composability is the key to creative innovation. But creators and developers can’t build on top of closed systems much like you can’t fix physical products that can only be opened by proprietary tools, like newer cars or iPhones.

Imagine if the inventors of the WWW decided to claim partial ownership of every webpage and take 50% of the revenue it generates (much like Horizon Worlds is now)—the Internet would not be as successful as it is today. Now, that we’re at the cusp of a new revolution, are we really going to asphyxiate it through walled gardens?

Business Models for Innovation

The question arises, is there an underlying trend of business models needing to increasingly focus on interoperability?

One interesting answer comes from Marc Andreessen of venture capital firm a16z and his former colleague Jim Barksdale. They point out that the tech industry is a cycle between bundling and unbundling. The early Internet creators were unbundling the media monopolies of the 20th-century. But, in a few years, new corporations like Google and Facebook arose which bundled together distraught Internet applications and technologies to meet user needs, creating new closed ecosystems.

Their empires grew and so did their bundles, and now we face new technologies like XR and blockchain which offer the opportunity to unbundle their hegemony in return. In a few years’ time, perhaps 2030 or 2035, the next wave of mega-corporations will bundle together the disjoint services and experiences of the Metaverse into a single package. Rinse and repeat.

Still, each major innovation in media brings more interconnectivity to the world, and that usually arises from interoperable standards. If we want the Metaverse to be something great, we can’t all be building our own worlds from the start. It’ll never gain users, it won’t be fun, and it won’t change the world.

As the user base increases and applications start to crossfade, network effects will kill anything that doesn’t interoperate. Imagine if there was a second WWW, with different web pages, with a different language. A single company can’t compete against a network of all other companies building the competitor, the open Metaverse.

Want to compete in the Metaverse? Subscribe to the My Metaverse Minute Channel: