Across my 40-year information technology (IT) career, I’ve had countless discussions about “transformation” with peers, managers, board directors, and even investors. Distressingly many of those conversations were along the lines of, “We have to do something!” rather than “Here’s the outcome we seek: How might we get there?”

Today let’s explore frameworks that can help management with transformation, in particular, digital transformation. Regular readers have many times seen my definition of digital transformation: a CEO-/board-led re-imagining of an organization’s culture, markets, products, customer experience, and employee experience that is driven — in part or entirely — by the promise or threat of technology.

While there are as many management frameworks as business books, here are a few of the most popular and powerful ones to help with digital transformation.

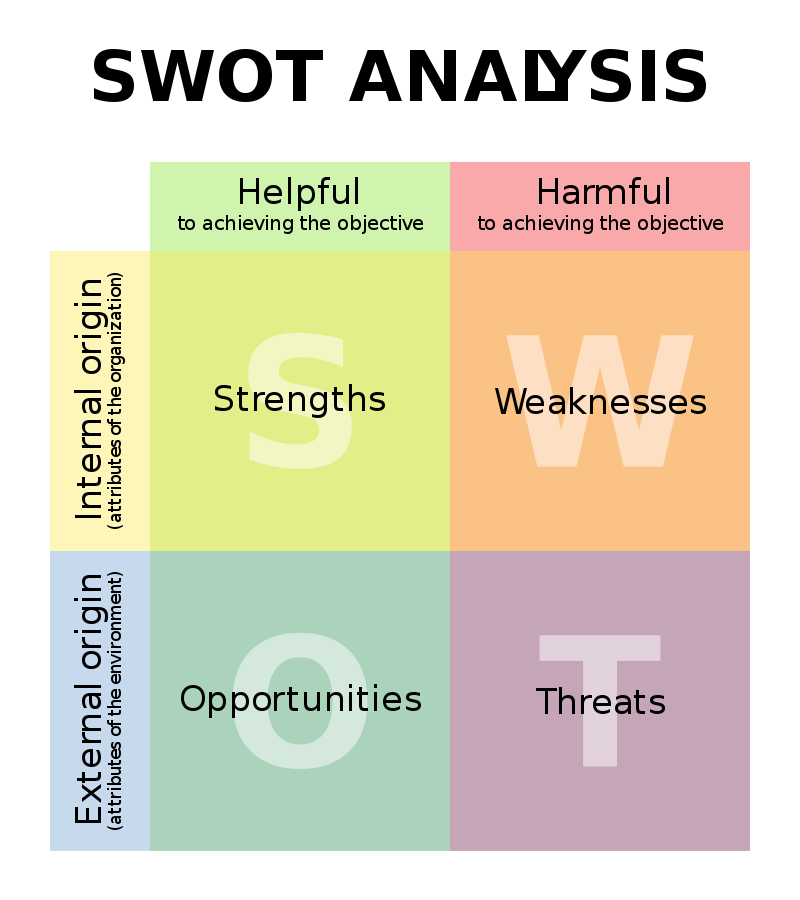

SWOT

SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis has been around for more than 50 years and reportedly came out of work done at Stanford Research Institute. This framework has been both overused and sloppily used. Most managers, therefore, discount the power of SWOT as an analytical tool — but they’re wrong to do so. Using SWOT properly requires doing two things that can be difficult: Clearly articulating “internal” versus “external” forces and honestly listing the organization’s weaknesses.

Separating internal (what we are good at/bad at) from external (what is happening to us from the world at large or actual/potential competitors) is a subtle, but powerful distinction. You can see a parallel to my definition of digital transformation. My definition highlights “the promise [of technology]”—that is, what we can do with our tech, and also highlights “the threat [of technology]”—that is, what others can do to us with their tech. Thus SWOT analysts must think hard about us vs. them, especially when contemplating digital transformation.

The second “hard thing” about SWOT is really hard. How many of us are both intellectually honest enough and brave enough to write down in a document — that might ohmygod be seen by the big bosses — things that our beloved organization suck at? In my experience, very few. (Shameless plug: This is one of the true values of hiring an experienced consultant. We have no fear of stating the truth, and we have no qualms about sharing our opinions with your C-suite).

In my experience, SWOT analysis can be a valuable tool for understanding an organization’s current state (or that of any functional part of the organization). As a CIO, your daily work involves evaluating the organization’s strengths and weaknesses because IT exists to fix weaknesses and shore up strengths. And a decent CIO is constantly scanning the horizon for existing and emerging technologies that competitors use or that their organization can use. So you’re already prepared! (And CEOs would be wise to include their CIOs in any SWOT analysis.)

The BCG 2×2 Matrix

The Boston Consulting Group developed the BCG 2×2 Matrix in the 1970s as an executive investment guide. It characterized business segments according to market share and market growth and outlined investment strategies for each quadrant. This is probably the most commonly known management framework, but here’s a bit of discussion for those who haven’t used it.

To succeed in a market today, you must have adequate market share to get brand recognition and return on scale. If you don’t have adequate market share, and don’t have a plan to grow it, then maybe you don’t want to be in that market. And to ensure future success, you want to be in growing markets or at least be growing in the market.

The two obvious quadrants are “stars” and “dogs”: Support the stars and disinvest in (or exit) the dogs. “Milking the Cash Cows” should be a phrase familiar to most managers, but maybe the concept isn’t clear: If you have a successful current position in a market lacking potential, use it to fund your future investments (which might mean maximizing margins, or even selling the business). “Question Marks” need deeper analysis: An excellent future opportunity but a weak current situation might mean “do a roll-up to acquire scale,” or it might mean “sell to a roll-up buyer,” or even might point the way to a digital transformation’s re-imagining.

When I’ve been involved in digital transformation planning, the question of where to invest —and more importantly, where to dis-invest to free up cash and management time — was vital. And the BCG Matrix helps management make the hard decisions that are so necessary to transformative projects.

Even a CIO with a “seat at the big table” might not have much input into the decisions represented by the BCG Matrix (even though you should have). But it’s essential that you do your own analysis of your organization — the data is out there, especially if you’re a C-suite insider—so you can a) opine thoughtfully if consulted, and b) be ready to move quickly when management decides where to invest and dis-invest.

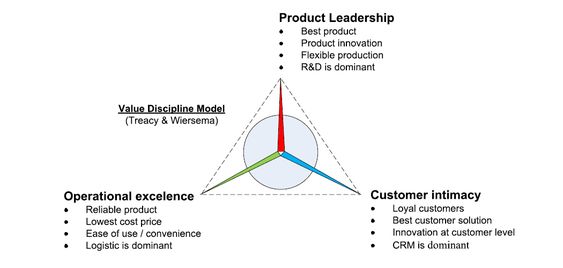

The ‘Value Disciplines’ Framework

The value discipline framework was created by Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersma in their 1995 book, “The Discipline of Market Leaders.” They did research that identified three basic value disciplines that successful firms organized around: operational excellence, product leadership, or customer intimacy. Their study showed that successful firms had to be “good enough” at all three values but at the same time had to excel at one and only one value. Walmart was a big success because they’re organized around operational excellence. Neiman Marcus was also successful because of its singular focus on customer intimacy. The point that stuck with me after reading the book (I’m a big fan of this framework!) was that a firm must literally design itself around its defining value and resist the urge to focus on two or more values . . . because organizing to be great at one value means you’re trading off the other two. Walmart isn’t organized to provide high-touch, individualized “customer intimate” experiences, just as Neiman Marcus isn’t organized to provide low-cost “operationally excellent” experiences.

In my career, I’ve seen many firms fail to match their stated value with their processes, branding, hiring/reward systems, processes, and technology investments — in other words, they don’t “walk the talk” to their detriment. As a CIO, you have a lot of influence over processes and systems. If you’re a true C-suite partner with a seat at the big table, the value discipline framework is a terrific tool for you to use. You understand how the organization actually works at a level few other executives know, and that knowledge is power. You can make a name for yourself helping align processes and technology tools with the organization’s principal value—and perhaps not investing as much in processes and tools that are contrary to that value (as opposed to the “let’s get better at everything” thinking that may not produce as much value).

Final Thoughts

Whichever framework one picks (and there are at least a half-dozen I haven’t covered here), using a structured analysis and decision-making process helps the organization make a sound, objective decision on transformation.

Want more insights into all things data? Visit the Data Modernization channel: