A year ago, the term ‘supply chain’ was meaningless to most people: Only the few of us involved with procuring, making, storing, shipping, and delivering goods ever saw the staggering complexity of the process whereby 99% of the world’s “stuff” got from the ground all the way to your table. Alas, in 2022 everyone knows the term…usually as part of the phrase “broken supply chain.”

What Does ‘Broken Supply Chain’ Mean?

What do we mean by ‘supply chain’ and who’s to blame that it’s broken? Wouldn’t it be nice if we could find the person or organization in charge and make them fix things? See, that’s the first problem: “supply chain” describes a messy, chaotic set of activities that are performed by literally billions of people spread across vast numbers of organizations, and in most cases, these activities have little to no central planning or control.

If you’re a computer geek, compare supply chains to the Internet. Who owns the Internet? Who keeps it running? Who do you call when “the internet breaks?” The supply chain is like that, except much messier because it involves tractors, cargo ships, power tools…and a billion-plus people literally all over the world.

It’s actually pretty amazing when you think of it. Somehow rocks dug from the ground get turned into metal that gets shaped into a part that gets installed in an airliner, or in the computer in front of me. A farmer somewhere in Brazil grew the coffee beans (using tools and supplies that someone else crafted) that got roasted and bagged and shipped to my home in Texas. Then, I brewed it using a coffeemaker assembled in the Netherlands that was delivered to me.

When you think about it, it’s a tribute to human ingenuity that supply chains function at all!

A Brief History of Supply Chains

Supply chains were very local for centuries. Stuff was dug up, transformed into something usable, and used by people within a few miles of one another. With steamships, then rail, then airplanes, supply chains lengthened and became global. Raw materials came from all over, particularly from countries that had lots of raw materials coupled with low costs (and often relatively lax regulations).

Meanwhile, the capacity to transform those raw materials was concentrated in more technically inclined areas. Over the last 60 years, the concept of ‘labor arbitrage’ was exploited to reduce production costs.

Globalizing the supply chain undoubtedly improved life all over the world. Low-cost countries with abundant natural resources found markets for products and labor, while consumers in more-developed countries saw lower prices and more product variety. There are many ‘negative externalities’ arising from such actions, and I’m not blind to them — but they’re far beyond the scope of this article.

However, shifting work to lower-cost countries, plus sourcing raw materials from all over the world, added huge complexity to the supply chain:

- Shipping went from local to regional to national to global

- Regulatory complexity increased (tariffs, pollution laws, building permits, customs)

- Language barriers multiplied

- National sovereignty issues were introduced (political aims, commerce for political aims, worries about embargos)

Supply Chain Complexities

OK, so the supply chain got very complex, and that’s been a good thing and worked well until now. What happened? Simple answer: pandemic disruptions and global instabilities. Let’s dig deeper.

Pandemic Disruptions

Pandemic disruptions can be divided into demand disruptions and supply disruptions. As the world abruptly shut down, everyone assumed demand would plummet. So, manufacturers slashed forecasts and canceled orders with suppliers.

For many reasons, including government support, demand for many goods didn’t drop. In some cases, demand increased A LOT (think Work From Home computer equipment). When farmers didn’t plant a crop based on canceled orders or energy firms stopped drilling, the demand rebound caught them flat-footed: ‘opening the tap’ again wasn’t quick or easy.

In other cases — like automobile ‘chips’ — manufacturers had switched already-strained capacity to other markets like consumer electronics. Of course, supplies were also disrupted by lockdowns and on-site workers either getting sick or staying home to avoid getting sick, which drastically constrained production and shipping.

Global Instabilities

Global instabilities take many forms. Cartels, like OPEC, can restrict supply to boost prices. Tariffs and regulations can make imported goods uneconomical or restrict their importation (does anyone need formula in the U.S.?). Conflicts can destroy productive capacity and lead to sanctions or embargos that restrict supplies.

Fixing a Broken Supply Chain

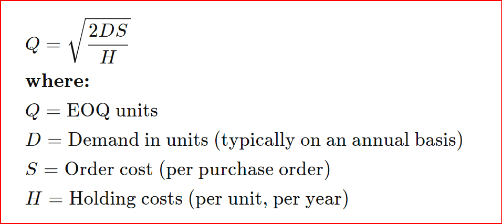

So, here we are. The pandemic is far from over, and global instabilities are on the rise. What can we do to fix our broken supply chains? It comes down to focusing on some mathematical ‘factors’ in the traditional Operations Research EOQ (Economic Order Quantity) model:

The above formula is a very simple version of a model that has been driving supply chain decisions for a century (actual models are far more complex and incorporate risk and non-monetary factors).

The key to how much and when to order is how much an order costs versus how much it costs to keep inventory (and to run out). When supply chains work normally, order cost is low and stockout risk is low, so inventory carrying cost gets minimized…leading to the famous ‘just-in-time’ fulfillment strategy that assumes a unit arrives at your loading dock at the same instant you use/ship the last unit in inventory.

From this description of where we came from and where we are today — and for the foreseeable future — the remedies should be obvious: Factor in the increased and less predictable risk of delivery disruption and adjust your ordering/inventory strategy accordingly:

- Increase ‘safety stock‘ kept on hand (and your ability to track inventory wherever you hold it).

- Reduce reliance on regions with instability risk (‘friend-shoring’).

- Shorten the length (distance and number of hand-offs) of the supply chain (on-shoring, near-shoring).

- Increase the number of inventory/distribution points to minimize single points of failure

- Refine your EOQ models to manage the new complexity (more variables, more risk adjustments, more real-time adjustments)

That’s all easy to say…but how do you get moving on this? I’m a CIO, so my answer is:

- Better, Faster Data: Too many facets of the supply chain are manual and after the fact. ‘Paperwork’ should be done away with in favor of real-time, structured data transmission. Start with your procurement process

- Are you triggering purchases based on customer order flow, project schedules, or other ‘upstream’ events? Or is someone looking at weekly or monthly reports and ordering what they think is needed?

- Are you receiving goods in real-time, so you know what just arrived and where it is?

- When you transship goods from one internal site to another, do they fall off the inventory? Or can you re-route a truck if something happens?

Next look at manufacturing/assembly:

- Are operations part of an end-to-end process flow? Or is WIP invisible?

- Can you forecast capacity versus demand across your entire footprint, so you can quickly move work if something happens?

Are your suppliers and subcontractors connected to your data process so you can see where they are at all times?

- More flexible systems (procurement, warehouse, transportation, order management).

- Connect the systems so orders drive procurement, which drives warehouse/transportation (you’d be amazed how many systems are connected via Excel).

- Be sure your expanded data needs (especially for real-time and partner data) are handled by your systems.

- Incorporate simulation, what-if analysis, and AI guidance into your systems to handle the increased complexity/reduced decision time.

The age of static ‘Supply Chains’ is over. Moving to a real-time ‘Supply Web’ that adjusts to the New Normal is imperative in the Acceleration Economy.

Want more tech insights for the top execs? Visit the Leadership channel: